We don’t often think of US Marines when we think about World War 2 in Europe. The Marine Corps, naturally, did the bulk of its work in the Pacific theater and probably survives today only because of the brutal, no-quarters warfighting the Old Breed did against the Japanese in places like Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Peleliu, and Iwo Jima.

There have always been efforts, principally by the US Army, to get rid of the Corps, but as Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal said on February 23, 1945, when speaking about the infamous Joe Rosenthal photograph: “The raising of that flag on Suribachi means a Marine Corps for the next five hundred years.”

But there were US Marines in the North African and European theaters, and one of them, Colonel Peter Ortiz, would receive two Navy Crosses after serving—as a French Legionnaire—in the Battle of France, and then later, as a US Marine, in the Tunisian Campaign and in Operation Jedburgh. Jedburgh was the joint operation between the British Special Operations Executive, the SOE, and the US Office of Strategic Services, the OSS, and the Free French Bureau Central de Renseignements et d’Action, to parachute agents into occupied France where they might lead the local maquisards in sabotage and disruption operations against the German Wehrmacht.

Colonel Ortiz

Peter Ortiz was born on July 5, 1913, in New York City. His mother was of Swiss decent, and his father a Spaniard, born in France, who was prominent in the French publishing industry. Ortiz spent the bulk of his childhood in southern California, and was later sent along with his sister, Inez, to French boarding schools. Ortiz was fluent in ten languages.

At 19, seeking something of the same adventure that would also drive Op Jedburgh men like George Millar–discussed in Part One–Ortiz joined the French Foreign Legion and was sent to the notorious training camp in Sidi Bel-Abbes, Algeria. By 1935—Ortiz was signed on for the minimum five year enlistment—he was promoted to Sergeant, and had earned the first of his 5 French Croix de Guerre fighting Berbers in the Moroccan Rif.

In 1937 Ortiz was discharged and came home to southern California, where he took various jobs in Hollywood as a technical adviser for war films.

In 1939, with the outbreak of World War 2 in Europe, Ortiz reenlisted in the Legion and was ultimately commission a lieutenant. As the Nazi’s poured into France, Ortiz was wounded in action and ultimately captured by the Germans. He spent a full year and a half as a POW, until he recovered sufficiently from his wounds, when he then escaped and ultimately found his way home to the United States.

In June of 1942, frustrated and impatient after waiting for the Army Air Corps to process his commission, Ortiz dumped the army plan and enlisted in the Marine Corps where, when he first fell out for recruit training at Parris Island, the DI’s were astonished to see a fruit salad of ribbons on his chest. He was ultimately recommended for a commission based on his exceptional experience and, in no small part, because of his unique language skills.

Ortiz was an accomplished parachutist, with 154 jumps to his credit while serving in the Legion, and the Corps sent him to New River to learn the Marine Corps way of jumping. “The Legion had its way and the Marine Corps had the right way,” he said. “I never minded jumping. Airplane travel always made me sick, so I was happy to jump out.”

After the allied landings in North Africa under Operation Torch, Ortiz was promoted to Captain and was assigned to the OSS. The OSS sent him to Morocco where he worked with British agents of the SOE along the Tunisian border in long-range reconnaissance missions known as Operation Brandon, a seesawing effort “to find and kill Germans.”

It was on one of these missions that Ortiz was nearly killed himself. Striking off alone, in knee-deep mud after a deluge of spring rains, Ortiz took a burst of machine gun fire that nearly destroyed his right hand and wounded him in the leg. On the ground, fighting for his life, Ortiz managed to launch a Mills grenade at the machine gun and a vehicle that were some 30 yards away and had him zeroed. It fell short. He followed the first grenade by hurling a Petard grenade–essentially a sticky bomb–that finally silenced the machine gun and knocked out the vehicle. He then crawled back, severely bleeding and in shock, to the base camp near Matleg Pass.

Maquisards in the Field

Ortiz was airlifted back to Washington, D.C., to convalesce, where OSS Commander William Donovan read Ortiz’ report covering his experiences. Donovan wrote on the first page: “Very interesting, please re-employ this man as soon as possible.”

Ortiz was then assigned to the Jedburghs, and on January 6, 1944, Ortiz, British Colonel H.H.A. Thackthwaite, and a Frenchman named Andre Foucault, a radio operator, parachuted into the Haute-Savoie region of France. Upon landing they removed their parachute rigs and, unlike many of the Jedburghs, donned their military uniforms—an act which made them the first Allied officers to appear in uniform, in France, since 1940. Thackthwaite, writing later about Ortiz, said “Ortiz, who knew not fear, did not hesitate to wear his U.S. Marine captain’s uniform in town and country alike; this cheered the French but alerted the Germans, and the mission was constantly on the move.”

In February, 1944, Ortiz was instrumental in rescuing four downed RAF officers that would ultimately lead to his being awarded the OBE, Order of the British Empire. The citation reads, in part: “In the course of his efforts to obtain the relase of these officers, he raided a German military garage and took ten Gestapo vehicles which he used frequently. He procured a Gestapo pass for his own use in spite of the fact that he was well known by the enemy.”

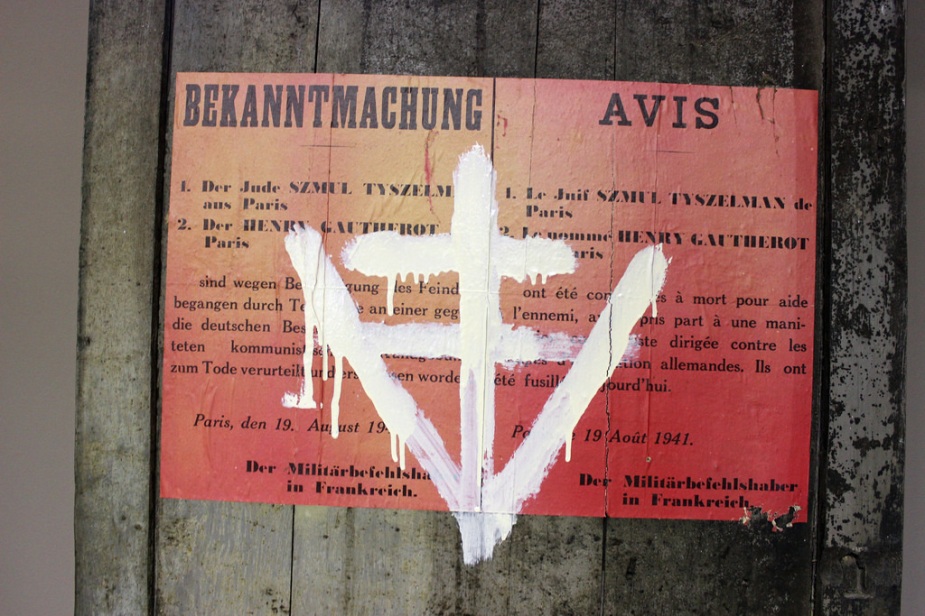

Vive Le Resistance

But Ortiz wasn’t finished capering. Although accounts of the escapade differ in some details, no one denies that what follows actually happened. A group of German officers had gathered in a small bar. These officers, from the German 157th Division, knew of Ortiz and also knew that his band of maquisards had been stinging them like hornets. They were getting drunk and were said to be cursing “the tall American Marine, the Allies, President Franklin Roosevelt, and the US Marine Corps”. Ortiz, however, was in the bar, dressed in civilian clothes. As a fluent speaker of German he would have understood everything. The legend says that Ortiz then returned to his safe house, changed into his uniform, donned a brace of 1911s, and put a raincoat over the ensemble. He then returned to the bar, aimed his pistols at the Germans and demanded a toast to both Roosevelt and the Marine Corps.

The accounts differ really on only one point, which is whether or not Ortiz then killed the German officers. Ortiz denied killing them. Later, he would say that he let them live because he wanted to boost his own legend amongst the Germans, and to sap their already flagging morale even further.

The first of his missions in operation Union I accomplished, Ortiz returned to England where he was awarded his first Navy Cross and promoted to major. On August 1, 1944, he returned to France with a team of fellow Marines and Joseph Arcelin, a Free French fighter. This operation, known as Union II, was to transform the Maquis into a direct-action capable combat unit, an evolution from their previous capabilities as an under-equipped guerilla fighting outfit.

Major Ortiz, Among the Maquisards, in Full Marine Uniform

It was shortly after his return that Ortiz, after battling a stubborn German unit on the outskirts of a small French village, found himself in a pickle he could not escape. Outgunned, and surrounded, Ortiz bravely walked across a field to negotiate the surrender of his unit, following guarantees that French citizens living nearby would not suffer reprisals, as had often been the case when maquisards were driven to ground.

Ortiz spent the remainder of the war as a POW, despite numerous attempts to repeat his earlier feat of escape. In 1946, he was discharged from active duty, though he remained a member of the Marine Corps Reserve until 1955.

Back in the United States, Ortiz returned to Hollywood, where two movies about his exploits were filmed, and where he appeared in numerous movies, including Rio Grande—where he played Captain St. Jacques–and in The Wings of Eagles, both starring John Wayne.

Colonel Peter Ortiz died in 1988, and is buried in Arlington. He was buried with full military honors, and his funeral was attended by representatives from both the French and British military, surviving members of Operation Union II, and his son, Lt. Colonel Pierre Ortiz, USMC.

They weren’t marines, but “Rogue Heroes” …the story of the founding and fighting of the British SAS in WWII will fire you and Cornelius up! A great read. Jim

On Fri, Jan 12, 2018 at 11:07 AM, Bunkhouse Chronicle wrote:

> Craig Rullman posted: “We don’t often think of US Marines when we think > about World War 2 in Europe. The Marine Corps, naturally, did the bulk of > its work in the Pacific theater and probably survives today only because of > the brutal, no-quarters warfighting the Old Breed did ag” >

LikeLike

Thanks Jim, I will check it out. I’ve recently gone the wonderful rabbit hole of WW2 War Correspondents, and keep learning new and fascinating things. You might like George Weller’s stuff…great original reporting from Africa to the Pacific.

LikeLike

Always moving and deeply humbling to learn about the lives of such remarkable men and their contributions to all of the rest of us that are fortunate enough to be here today. I pray that we never forget what has been afforded us by all those that have gone before with absolute selflessness and conviction. I pray we never lose our ability to appreciate and feel deep gratitude for what we have been given by the sacrifice of so many. I pray for the respect that has been earned by the men and women of this Country and for our Country itself. I pray that if we fail to remember the opportunities we all have today because of men like this our future is lost forever.

LikeLike

I couldn’t agree more. I’ve fallen down this rabbit hole, which began with reading the works of the better known WW2 correspondents. Those accounts are fascinating and open up some fine windows into history.

LikeLike

Excellent account of a tremendous man. I find it amusing that the “right way” the Marine Corps had (and still has) for paratrooping is actually US Army Airborne School at Fort Benning. It’s only after a Marine (or a Sailor, Soldier or Airman) gets their wings that they would go to New River for further training.

LikeLike

True enough. I’m not sure if the same pipeline was in use in 1944, and he already had 150+ jumps. But hey, the Corps has its pride too.

LikeLike

The Corps has earned its pride. Thanks again for the great read.

LikeLiked by 1 person